Cross Country Risk Management for Busy Airspace

- Asst.Prof.Capt.Dr. Gema Goeyardi,MCFI,ATP

- Dec 30, 2025

- 5 min read

If you have ever flown a cross country near a major metro area, you know the feeling.

The weather is changing, frequencies are busy, airspace transitions pile up, and your head is doing ten jobs at once.

Cross country flights are where pilots build experience, but they are also where small planning mistakes can stack up into high workload.

As a flight instructor, I do not teach cross country planning as a paperwork exercise.

I teach it as risk management.

Because if you can manage risk on a busy cross country flight, you are building the mindset that keeps you safe for the rest of your flying life.

This article breaks down a simple, repeatable framework for cross country risk management, with special focus on busy airspace and real world GA operations

What “Cross Country Risk Management” Means

Risk management is not fear.

It is awareness and control.

Cross country risk management means:

identifying hazards before departure

assessing how those hazards interact

creating mitigations that protect safety margins

setting clear decision points

In busy airspace, risk tends to come from:

workload

distractions

airspace complexity

traffic density

weather pressure

time pressure

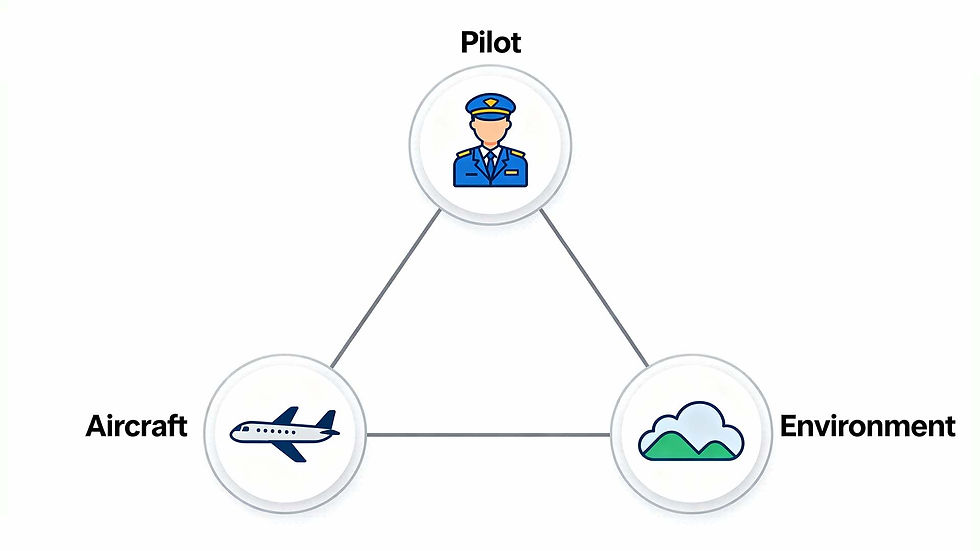

The Three Risk Layers Every Cross Country Has

Layer 1: Pilot

fatigue

proficiency

currency

stress

recent flying experience

Layer 2: Aircraft

maintenance status

performance margin

fuel planning

avionics reliability

limitations

Layer 3: Environment

weather

terrain

traffic

airspace

airports and alternates

NOTAMs and restrictions

Most bad outcomes happen when all three layers have small weaknesses at the same time.

Your job is to strengthen one layer when another is weak.

Busy Airspace Adds Unique Risk

In quiet airspace, a pilot can “figure it out” as they go.

In busy airspace, you have less time and less tolerance for indecision.

Here is what changes:

Frequency workload

You may be switching:

ATIS or AWOS

ground

tower

departure

approach

center

local advisories

Airspace transitions

You might cross:

multiple class B shelves

class C rings

MOAs

restricted areas

special flight rules areas

Traffic density and closure rates

Busy airspace means higher closure rates.

Your scan needs to be aggressive and your flight path predictable.

Decision windows are shorter

If weather drops or a runway changes, you may have minutes to adjust.

That is why planning matters.

A Practical Cross Country Risk Management Framework

Here is a simple framework pilots can actually use.

Step 1: Build a “big picture” plan

Ask:

what is the route?

what is the weather trend?

what are the airspace pinch points?

where are the best alternates?

what is the time pressure?

Step 2: Identify top five hazards

Limit it to five.

If you list twenty hazards, you will not manage any.

Examples:

marginal ceilings near destination

strong winds in a narrow corridor

class B transition with heavy traffic

fuel margins tight due to headwinds

pilot fatigue after a long workday

Step 3: Create mitigations

For each hazard, create a real mitigation.

Example: Hazard: marginal ceilings Mitigation:

set a higher personal minimum

plan an alternate with better weather

brief a diversion point

depart earlier

Hazard: busy class B transition Mitigation:

file flight following

pre-brief frequencies

prepare a “stay outside B” route

Step 4: Set decision points

Decision points prevent “press on” bias.

Example: “If ceilings drop below X at this waypoint, we divert.”

Step 5: Brief it like a crew

Even if you fly solo, brief yourself.

In busy airspace, mental rehearsal matters.

Weather Decision Making for Busy Cross Countries

Weather is still the top driver of GA accidents and incidents.

For busy airspace flights, focus on:

Trend, not snapshot

A single METAR is not enough.

Look at:

what it was doing

what it is doing

what it will do

Wind and turbulence planning

Busy airspace often means:

more controlled approach paths

less flexibility

stronger crosswinds near coastal airports

Convective planning

If storms are possible:

plan routes that allow outs

avoid narrow corridors with no alternates

brief escape options

Personal minimums are your safety valve

In busy airspace, the margin matters.

Higher personal minimums reduce workload and risk.

Fuel and Alternates: Where Pilots Get Trapped

Busy airspace can create fuel traps.

Example:

holding for sequencing

long vectors

delayed approach

unexpected runway change

H3: Risk management fuel mindset

Do not plan “legal fuel.” Plan “comfortable fuel.”

If you land with the legal minimum but stressed and rushed, you planned wrong.

H3: Alternate strategy

Pick alternates that:

have multiple runways

have services you may need

have better weather patterns

are outside the busiest constraints

Pilot Insight (Instructor Notes From the Real World)

Here is the pattern I see.

The pilots who struggle on busy cross countries do not lack skill.

They lack bandwidth.

They have not pre-briefed:

frequencies

airspace entry plans

contingency routes

diversion airports

So the flight becomes reactive.

The pilots who do well are proactive. They are not perfect. But they have prepared enough that surprises feel manageable.

One practical trick: Write your “top three next actions” on your kneeboard.

Example:

If weather drops, divert to X

If denied class B, route around via Y

If fuel margin shrinks, stop at Z

This reduces decision pressure when workload spikes.

Action Checklist (Cross Country Risk Management Guide)

Busy Airspace Cross Country Checklist

Pilot

rested and hydrated

currency checked

personal minimums set

Aircraft

fuel planning with margin

performance calculated for expected winds and runways

avionics checked

alternate plan if a system fails

Route and airspace

identify class B and class C transitions

pre-load frequencies

brief a “no clearance” route

request flight following early if possible

Weather

review trend and forecast

identify ceilings and visibility risk

brief convective avoidance

set diversion decision points

Alternates

select at least two alternates

brief approach and runway options

consider traffic and services

Mental rehearsal

brief taxi, departure, airspace transitions

visualize high workload moments

identify “pause points” to slow down

FAQ (SEO Style Questions)

1) What is cross country risk management?

It is the process of identifying hazards, assessing risk, and building mitigations and decision points for a cross country flight.

2) Why is busy airspace more risky for cross country flights?

Because workload increases, decision windows shrink, and traffic and airspace complexity reduce flexibility.

3) What are the top hazards on busy cross country flights?

Weather trend changes, airspace transitions, traffic density, fuel margin issues, and pilot workload and fatigue.

4) What is the best ADM checklist for cross country flying?

A practical ADM checklist covers pilot, aircraft, environment, route, weather, alternates, and decision points.

5) How do I manage airspace transitions safely?

Pre-brief frequencies, know the airspace structure, have a route around, request flight following, and keep the airplane predictable.

6) How much fuel margin should I plan in busy airspace?

Plan comfortable fuel, not just legal fuel, because sequencing and vectors can add unexpected time.

7) What is the biggest cross country planning mistake pilots make?

Failing to build real decision points, then pressing on when conditions degrade.

Conclusion and Community CTA

Cross country risk management is not about being cautious.

It is about being professional.

Busy airspace flying is where pilots learn how to manage workload and make solid decisions. The better your planning, the more mental bandwidth you have when something changes.

If you fly cross countries in busy airspace, share with the IFPA community:

your top risk management habit

your favorite planning tool

one lesson you learned from a busy cross country flight

That conversation helps everyone fly safer.